The Yoshihara Tradition & The traditional craft of Japanese sword making

“The Japanese sword is a symbol of bushido, and signifies the spirit of Japan”

From a sword inscription by Yoshihara Kuniie dated 1944

As Dr. Sato Kanzan is known to the sword world as the saviour of Japanese swords from destruction by the allied forces, so Kurihara Hikosaburo (Akihide) is known as the

saviour of Japanese swordmaking. Born in Kanma, Tochigi prefecture in 1879, Kurihara’s interest in Japanese swords stemmed from his childhood.

His father, a keen sword enthusiast, invited a prominent member of the Inagaki family of swordsmiths to the forge he had built on his estate.

During his adolescent life, through a politician friend of his father, he went to live in Tokyo with Okuma Shigenobu (a future Japanese Prime Minister) whilst he attended

Aoyama Gakuin, a famous Tokyo English school. He later went on to become a member of the national diet (parliament).

As a politician, he had a reputation for being quite flamboyant. He once brought a live snake into parliament and threw it at a member of the

opposition during a heated debate. Like his father, Kurihara, concerned that the traditional craft of Japanese sword making was being lost, was eager to remedy the situation.

The craft had suffered somewhat since the hatorei decree during the Meiji period, which banned the wearing of swords by samurai in public. The demand for swords had steadily decreased since that time and the number of swordsmiths had decreased along with it.

In 1933 the Japanese government realised the craft was endangered. The Prime Minister, Saito Makoto, aware of Kurahara’s knowledge and enthusiasm for Japanese sword making, asked him to undertake a project devoted to increasing the number of Japanese swordsmiths.

Kurihara’s answer was to open the Nipponto Tanren Denshu Jo(Japanese Sword Forging Institute) on the grounds of his estate in Akasaka, Tokyo on the 5

th of July 1933.

Kurihara had no real formal training as a swordsmith, but enjoyed the yaki-ire process of quenching the blade. As a result, he became quite specialized in this aspect of sword making. Despite the fact that he lacked formal training, Kurihara, took the art name of Akihide, and placed himself in the position of Head Chief Instructor of the Denshujo.

He employed another swordsmith, Beppu Kiyoyuki, as Chief Instructor. Kiyoyuki’s time at the Denshujo was quite short, as he too was not a fully-fledged swordsmith. He’d had some training, and was accustomed to working with tamahagane(the type of steel produced for Japanese making), but this was mainly due to his formal training as a

toolmaker.

In 1934, Kurihara invited one of the most famous smiths of the period, Ikkansai Kasama Shigetsugu, to become the chief instructor of the Denshujo. This was perhaps the most influential smith to teach there in its entire history. He also had the greatest impact on the students and teachers alike. Shigetsugu, born Kasama Yoshikazu on April 1, 1886 in

Shizuoka, started his apprenticeship under his uncle Miyaguchi Shigetoshi in 1899. In 1903 he entered the Tokiwamatsu Token Kenkyujo, on the estate of Toyama Mitsuru, to study under Morioka Masayosh. Later he went on to study metallurgy whilst collaborating with Dr. Tawara Kuniichi in formal research on the composition of

Japanese swords.

Tazawa built a special laboratory in Tokyo University for the project.

The results were published in a book called Nihonto no Kagakuteki Kenkyu(Scientific Research of the Japanese Sword), which remains to this day a definitive scientific work

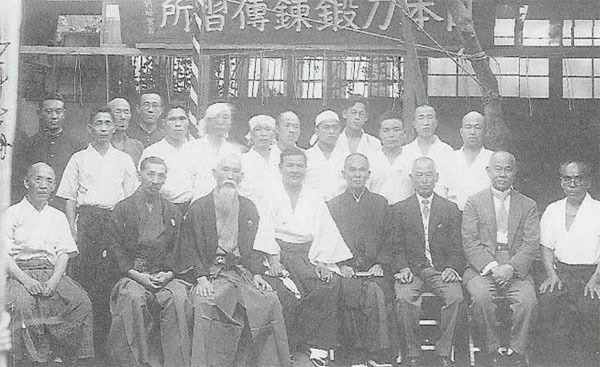

on the subject. First Graduating class of the Denshujo.

Front Row far left: Kasama Ikkansai Shigetsugu; 3rd from left: Toyama Mitsuru, 4 th from the left: Kurihara Hikosaburo (Akihide); far right: Kiyoyuki Beppu; 2 nd

from right: Dr Tazawa Kuniichi. Back row—far right: Yoshihara Kuniie; 2 nd from right: Yoshihara Masahiro; 6 th from right: Yoshihara Kuninobu.

Shigetsugu worked mainly in the Bizen and Soshu traditions of swordmaking, which influenced many of the Denshujo’s students’ later work. It is recorded that full-time

students of the Denshujo received the character Aki (ত) from Kurihara (Akihide) to use as part of their Denshujo art names, whereas some direct students of Shigetsugu have

been allowed to use ‘Ikkansai’(Ұ؏ࡈ) or ‘Tsugu’(ܧ).

This may not be a clear definition of terms as many of the “Aki” smiths also would have learned their skills from Shigetsugu during his term as chief instructor.

As well as a master swordsmith, Shigetsugu was also a very skilled carver of horimono (decorative blade carving). He often made swords on the estate of Toyama Mitsuru, a

right-wing nationalist and founder of the Black Dragon Society. A recently rediscovered blade made by Shigetsugu on Mitsuru’s estate had been commissioned by

Nagamatsubara Hiroshi of Nihon University.

This sword was a gift for the Governor General of Germany–Adolf Hitler–and was inscribed accordingly. The sword also had one of Shigetsugu’s wonderful horimono, one of the five Buddhist Kings of Light from esoteric Buddhism– Fudo Myo-O (Acala). Fudo Myo-O, The Immovable, is the patron deity of Japanese swordsmen.

He has a fierce expression whilst clutching his sword in his right hand and a rope in his left and is surrounded by a halo of flames. The rope is to bind the enemies of enlightenment, while his sword, with a three-pronged Buddhist ritual instrument called a vajraas the handle, is to cut through the illusionary world to the

ultimate reality.

Below this fierce exterior is an immovable nature, to which swordsmen wish to aspire. Ikkansai Kasama Shigetsugu was only to work at the Denshujo for two years. It would seem there was some kind of disagreement between Shigetsugu and Kurihara.

This could have been for a number of reasons. Shigetsugu was an accomplished prominent contemporary swordsmith. Kurihara, on the other hand, had never been fully trained in the craft. However, as is traditional within Japanese crafts, teachers have licence to sign students’ works. As Kurihara was the leader of the Denshujo, it was probable that he performed yaki-ire on his students’ swords and signed them as his own work.

Therefore, it is likely this was also the case with some of Shigetsugu’s swords. This was probably a thorn in the side of a smith of Shigetsugu’s expertise. There are also indications of a cash flow problem, which included Shigetsugu’s wages. The Denshujo was a self-financed organisation, which was initially started through sponsorship.

Kurihara, at times, had to sell some of his own belongings to continue the project.

As the rift between these two very strong characters grew, Shigetsugu taught at the Denshujo less, until in 1935, he stopped attending completely. This did not favor at all

well with Kurihara, who was a very prominent figure in the sword world and as an expolitician, was extremely well connected in high society.

He used his influence to try to keep Shigetsugu out of the spotlight by not including him in his monthly publication that he produced called Nihonto Oyobi Nihon Shumi (Japanese Swords and Japanese Hobbies). This was a current events publication for sword enthusiasts.

The publication started a year after the initial split and continued through to 1945, so it is very surprising to see one of the period’s greatest smiths and former Chief Instructor of the Denshujo rarely mentioned within the publication.

In response, Shigetsugu boycotted any sword events arranged by Kurihara. This doesn’t seem to have affected Shigetsugu too adversely, as he still made swords for members of the imperial family and on the estate of one of Kurihara’s good friends, Toyama Mitsuru, with whom he went on to co-found the Tokyo Swordsmiths Association.

Shigetsugu died in 1966. He was 80 years old.

At the end of the allied occupation Kurihara once again was an important factor in the revival of swordmaking, successfully petitioning the government for the resumption of

sword manufacture. You will find that most of the smiths today would be able to trace their lineage through Kurihara or his work to keep swordmaking alive in the early and

mid parts of the 20 th century.

Living National Treasures Miyairi Akihira and Amata Akitsugu are only two of the post-war swordsmiths who have been touched by Kurihara’s efforts.

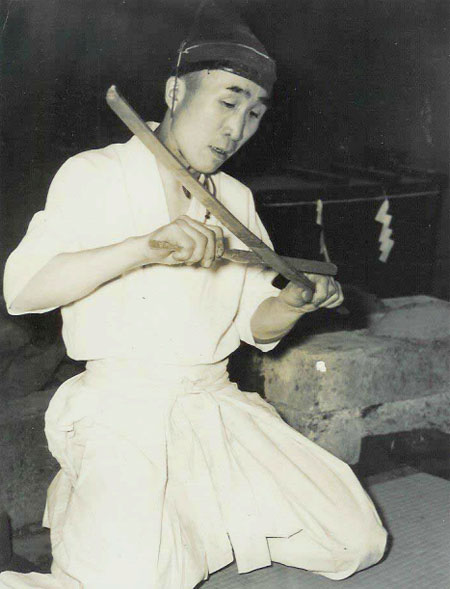

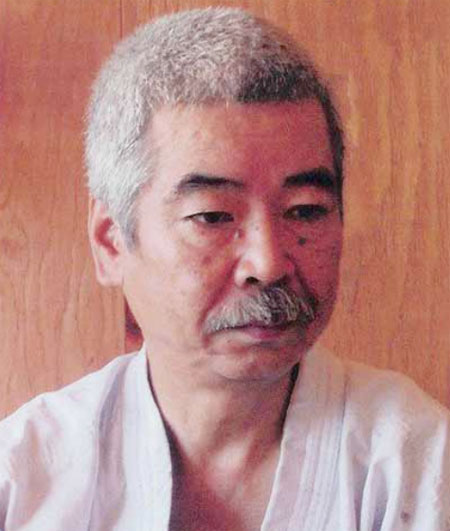

Yoshihara Kuniie 1st Generation (1894-1970)

The first student to sign up at the Nipponto Tanren Denshu Jo was 38 year old Yoshihara Katsukichi, who would later become known as Kuniie. Born on July 26, 1894 at the foot of Mt. Tsukuka in Ibaraki prefecture, Kuniie was the son of a seventh generation hard edge toolmaker.

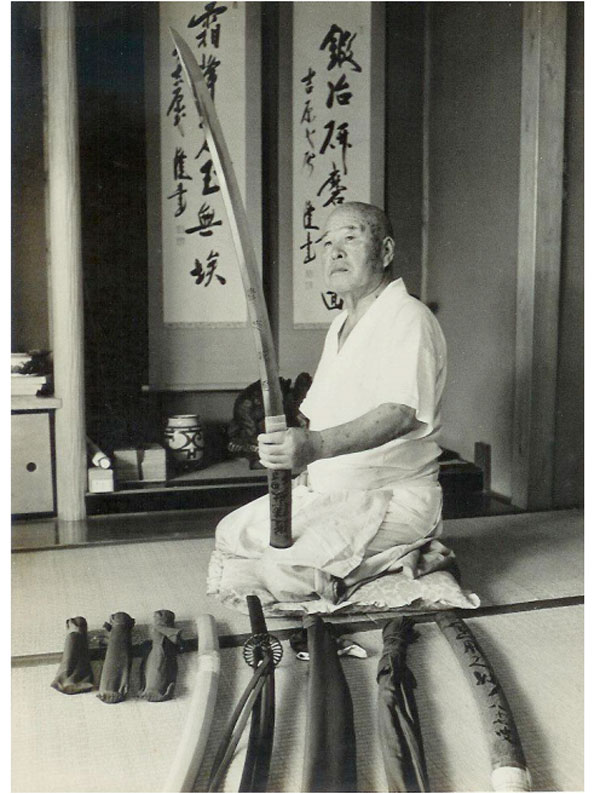

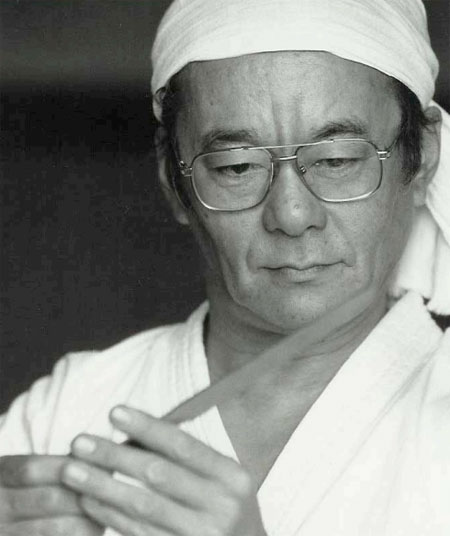

Yoshihara Kuniie

Although expected to continue the family business in Ibaraki, he moved to Tokyo, where he completed his toolmaking apprenticeship. Kuniie spent the next twenty years concentrating on developing his own tool manufacturing business, raising his family, and preparing his son Masahiro to succeed the family business, until one day he saw an advertisement placed in a national newspaper by Kurihara seeking apprentice swordsmiths.

This appealed greatly to Kuniie as he had already tried to make swords on his own, and (through his toolmaking experience) understood the mechanics of tamahagane very well. He immediately responded to the advertisement and was accepted as the first official student of The Nipponto Tanren Denshujo in the fall of 1933.

Kuniie’s younger brother, Kuninobu (given name Shinsaburo) and his son, Masahiro (sword art name Masazane) also joined the Denshujo shortly after him. With the increased Japanese military activity in China and an impending second world war, being a swordsmith was fast becoming a secure way of making a living.

Outside Kuniie’s home and workshop in Setagaya. Masazane stands behind Kuniie Both Yoshindo and Shoji were born here.

Kuniie’s first instructors at the Denshujo were Kurihara and Kiyoyuki. It is unlikely however, that Kiyoyuki was able to teach him very much about sword production, as Kiyoyuki had not served a real swordsmith’s apprenticeship and Kuniie was at least Kiyoyuki’s equal in tool manufacture. Kuniie was given the art name ‘Akihiro’ by Kurihara.

He also used this name whilst teaching at the Nihonto Gakuin and at the forge of Toyama Mitsuru. However, Kuniie’s real mentor in swordmaking techniques was Kasama Ikkansai Shigetsugu. He was taught by Shigetsugu the fundamentals of making swords in the Bizen and Soshu traditions. Many of Kuniie’s extant works are in the Bizen and Soshu traditions, as are Shigetsugu’s.Kuniie also worked in the style of Kiyomaro, a famous Edo period smith.

After graduating in the first class from the Denshujo, Kuniie quickly cultivated a good reputation. As his skills were in great demand, he soon became an instructor at various institutions. In 1937, he became an auxiliary teacher of the Kyushu University Kingakubu Nihonto Kenkyujo.

The following year, he opened his own workshop, the Nihon So Tanrenjo, at his residence in Setagaya, Tokyo. Around the early 1940’s Kuniie was working part-time in many places. He was also a contract smith for the Japanese Imperial army (Rikugun Jumei Tosho).Following in his mentor’s footsteps, he became an instructor smith at the forge on the grounds of Toyama Mitsuru’s estate (the Tokiwamatsu Tanren Kenkyu Jo in Shibuya, Tokyo) after Shigetsugu had moved on to another venue.

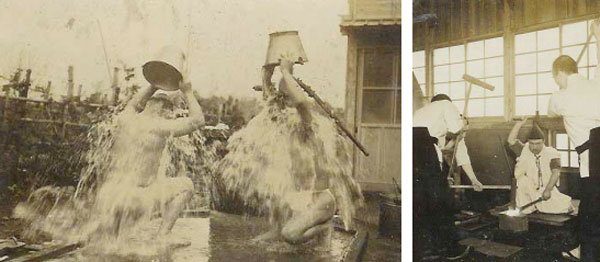

In 1941, Kuniie was appointed by Kurihara as chief instructor of the newly formed Nihonto Gakuin (Japanese Sword Institute) at Sagamihara-cho, Zama (Sobudai), Kanagawa Prefecture. As part of the opening day ceremonies he gave a demonstration of tameshiigiri (cutting test).

Opening ceremonies at the Nipponto Gakuin. Kuniie demonstrating tameshiigiri.

By 1943 Kuniie had gone on to become a swordsmith instructor for the Japanese Imperial Army at the Tokyo Dai Ichi Rikugun Zoheisho, the military arsenal in Akabane, Tokyo. Here he chose to use yet another art name—Nobutake. His job was to train army smiths and inspect and acquire swords made in the kanto region (Tokyo and surrounding areas).

The opening ceremony of the forge at the Tokyo Dai Ichi Rikugun Zoheisho.

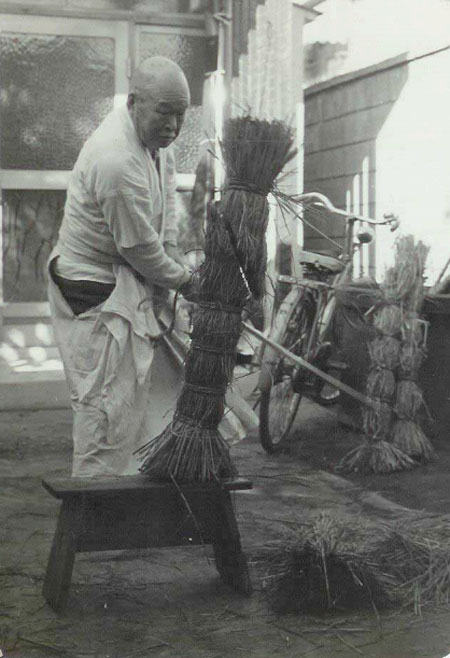

The swords he made there are usually inscribed ‘Tokyo Dai Ichi Rikugun Zoheisho Yoshihara Nobutake’ Kuniie Akihiro Akihiro (sosho-mei) Kuniie Kuniie (sosho-mei) Nobutake Kuniie inspecting his work. Kuniie was famous for his skill at performing cutting tests Kuniie at his forge in Katsushika-ku Kuniie and another smith performing Shinto rituals and making swords at the Nipponto Gakuin.

Various Inscriptions used by Yoshihara Kuniie

The Nihonto Gakuin was closed at the end of WWII in 1945. At that time the allied occupational forces enforced a ban on swordmaking and related activities. During this period Kuniie returned to toolmaking, starting a very successful crowbar manufacturing business with his son Masahiro. In 1953, when the ban was lifted, Kuniie returned to the craft.

However, as the Japanese economy was in bad shape, he did not produce very many swords, concentrating instead on his original profession as a toolmaker.

In 1955, eighteen years after beginning his apprenticeship (due to the new laws on swordsmithing that were enforced by the post-occupation Japanese government) Kuniie was forced to apply for and obtain a swordsmith’s licence. By 1964 the economy had recuperated somewhat and he was able to leave the family business in the hands of his son Masahiro and return to swordsmithing full-time.

Kuniie and another smith performing Shinto rituals and making swords at the Nipponto Gakuin

However, from this time on he did not produce very many swords, but spent his time training his new apprentice Shimizu Tadatsugu and his two grandchildren Yoshindo and Shoji in the craft. Kuniie passed away in 1970 at the age of 76. Kuniie was a major driving force of swordsmithing in the Showa period.

He believed that a good swordsmith hones one’s skill by making many blades—not mass producing works, but concentrating on the nuance of the swordmaking process. His legacy endures through the skill of some of the top swordsmiths in Japan today. Four of the smiths in his lineage have been appointed mukansa, an accolade that places them among the elite of their field.

Kuniie inspecting a blade in 1969.

Kuniie was famous for his skill at performing cutting tests

Kuniie at his forge in Katsushika-ku

Kuninobu forging swords with Masahiro as sakite (hammer-man) in the rear right of the picture

Yoshihara Kuninobu (1899-1983)

Kuninobu forging swords with Masahiro as sakite (hammer-man) in

the rear right of the picture

There is not much information available about Kuninobu. He had no children to succeed him and during the post war turmoil and the looming allied occupation in Japan many records were lost or destroyed to prevent the information getting into the hands of the allied forces.

Kuninobu followed his older brother (Kuniie) to Tokyo from Ibaraki searching for work as a toolmaker. Both he and Kuniie’s son Masahiro joined The Nipponto Tanre Denshujo shortly after Kuniie. Although he initially signed his work ‘Akimitsu’, he opted for the name Kuninobu around 1939—around the same time his brother changed his name to Kuniie.

Kuninobu also worked at the Nihonto Gakuin. As was the case with many smiths, the poor post war economy and the allied occupation’s ban on any sword-related activities

prevented him from returning to swordmaking However, despite his relatively short period as a swordsmith, there are still quite a few extant works of Kuninobu.

Yoshihara Masazane (1917-1980)

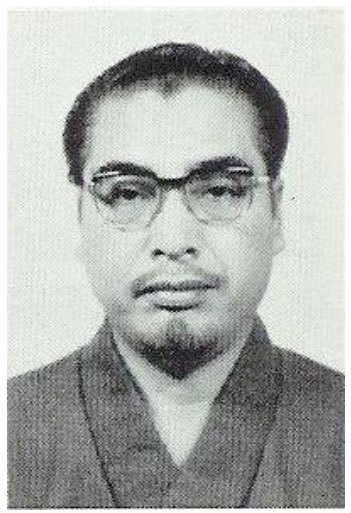

Yoshihara Masazane

Yoshihara Masahiro was the son of Kuniie and father to Yoshindo and Shoji (Kuniie III). Masahiro was also a member of the Denshujo and the Nihonto Gakuin. Masahiro originally signed swords as Masazane . He briefly took the Akihiro name in 1939, the year after his father had changed his name to Kuniie, but returned to using Masazane the following year.

Masahiro made swords in the styles of the Horikawa school, the Mishina School, Bizen den and in the style of Kiyomaro. Masahiro only made swords until 1945, when the allied forces banned swordmaking. It was at this time that Masahiro returned to the toolmaking business with his father and began making crowbars.

However, in 1953, when the ban was lifted, he did not return to the craft like his father, but continued to work as a toolmaker and train his son Yoshindo in the family business. This was the fate of many smiths who stopped producing swords at the end of the war.

These smiths are known as the ‘lost generation’. Although Masahiro never produced any swords himself after the war, he actually applied for and obtained his swordsmith’s licence in 1976 in the art name of Kuniie. There have been a few occasions however, when Yoshindo and Shoji have produced blades in the style of their father and signed Kuniie.

This is a common practice within swordsmith schools in Japan, as these blades are considered daisaku: made in the same style of the teacher and signed in his name with his full permission—typically by his students. He died in 1980 aged 62. His extant works are quite rare.

Shimizu Tadatsugu (1921-1998)

Shimizu Tadatsugu

Shimizu Tadatsugu often signed his blades with the three character inscription ‘Tadatsugu saku’ (made by Tadatsugu). He became an apprentice to Kuniie I in 1963 and obtained his swordsmith’s licence in 1968. Working in the soshu style, he particularly favored the Samonji school of Chikuzen provence from the Nanbokucho period (1333-1392).

He also produced works in the style of Kiyomaro. In 1969 he entered the Nihon Bijutsu Token Hozon Kyokai’s Shinsaku-meitoten (Modern Swordsmiths’ Exhibition), but did not win an award until the following year. He went on to win the Award for Effort four times, the Award for Excellence three times, and the Nyusen Award once.

The official opening ceremony party of the Nihonto Tanren Dojo. Front row; 4 th from left Honami Kohaku, 7 th Dr Sato Kanzan, Yoshindo, Kunzan Homma, Shoji. Back row 11 th from right Nobuo Ogasawara

The Nihonto Tanren Dojo

The official opening ceremony party of the Nihonto Tanren Dojo. Front row; 4th from left Honami Kohaku, 7 th Dr Sato Kanzan, Yoshindo, Kunzan Homma, Shoji. Back row 11th from right Nobuo Ogasawara

On June 16, 1971, in honor of their grandfather, Yoshindo and Shoji opened the Nihonto Tanren Dojo; a swordsmith workshop on the grounds very close to where their grandfather’s workshop had been in Katsushika-ku, Tokyo.

At this time the Japanese economy had been recovering from its post-war depression, interest in swords had regained its popularity, and collectors were once again able to afford such luxuries.

However, making a living as a swordsmith was still a tough route to take. In spite of this, Yoshindo and Shoji closed the crowbar business and took their chances as full-time

swordsmiths. The Nihonto Tanren Dojo was opened with full ceremony and attended by the most influential scholars of the Japanese sword world.

Dr Sato Kanzan and Homma Kunzan (Junji), the directors of the NBTHK, were the principle guests, along with Honami Kohaku, whose family had been appraising swords since the 15 th century.

Also in attendance was a young Nobuo Ogasawara, a future great scholar and senior curator of Japanese swords at Tokyo National Museum. Inside the dojo there is a plaque hanging on the wall. It is handwritten and signed in the calligraphy of Dr. Sato Kanzan. It reads ‘Kote nasu hyaku ren tetsu’(with a hundred times forging, comes good steel).

Yoshindo has had many visitors to the workshop, including a one-time visit by Sweden’s monarch King Carl XVI Gustaf. The Yoshihara brothers originally shared this forge, but Shoji currently has his own forge at his residence in Nishi Mizumoto.

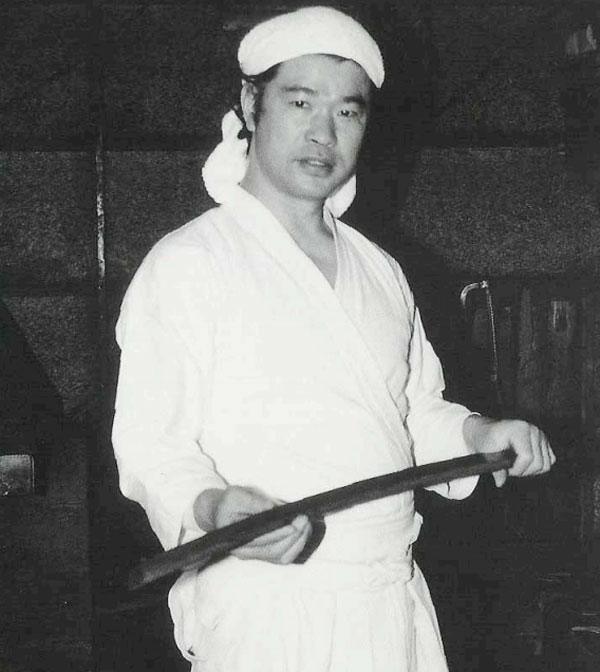

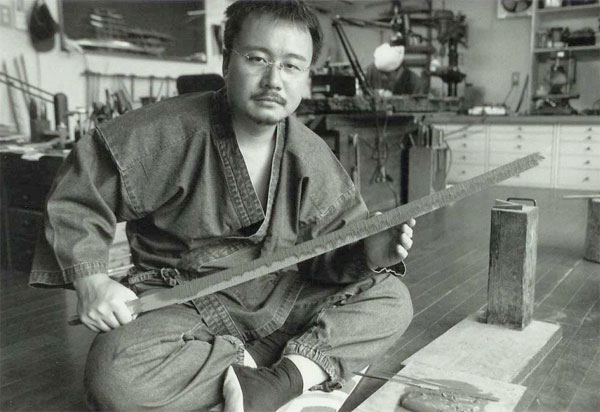

Yoshihara Yoshindo

Yoshihara Yoshindo

Yoshindo was born in Tokyo on the 21st of February 1943. Yoshindo didn’t join his brother and grandfather in the workshop full-time until he was 24 years old. Even though he had spent much time in the workshop with his grandfather from the age of 9, as the eldest son it was his responsibility to help his father continue the family business of tool manufacture.

Yoshindo, along with his brother Shoji, had become a licensed smith in 1965. They made a great impact on the Japanese sword world. They were both young and dynamic, having gained swordmaking experience from an early age. In 1973 Yoshindo was the first-ever winner of the Prince Takamatsu Award at the national swordsmithing

competition (Shinsakumeitoten).

As a result he received a request to perform cutting tests with the award-winning blade before the Prince. The Prince had wanted to ensure that modern swords would excel functionally as well as aesthetically before giving the award. Once the test had been completed, the Prince (convinced of their cutting bility) never requested a cutting test again.

Yoshindo performing tameshigiri(test cutting) in front of Prince Takamatsu in 1973

Yoshindo went on to win the Takamatsu Award on a further two occasions.

In 1980 Yoshindo was invited to Dallas, Texas, where he demonstrated sword forging for over a month. The following year, the swords he made in Dallas were purchased by the Boston and New York Metropolitan Museums.

In 1982, after winning first prizes seven times at the annual swordmaking competition, Yoshindo was awarded the rank of Mukansa (above competition level). On two occasions he received orders for his swords from Japan’s premier shrine, Ise Jingu.

The swords were made with full ceremony of Shinto ritualism and are considered ‘sacred swords’. In 1987, he co-wrote the first of three books with his American friends, Leon and Hiroko Kapp—a definitive sword book in English, called “The Craft of the Japanese Sword”.

Yoshindo has also featured in numerous documentary programs.

In one such video, a sword made by Yoshindo was used in a test cutting demonstration on a Japanese samurai helmet. It cut 5 centimeters into the helmet with no damage to the sword.

In 1998 Yoshindo and Shoji were made intangible cultural properties of the ward in

which they live, Tokyo’s Katsushika ward. In March, 2004, Yoshindo was elevated to the level of Tokyo no mukei bunkazai,or intangible cultural property of Tokyo.

He received his award with due ceremony at the civic center in Tokyo. He has made blades for several national institutions and exhibited at many venues in Japan. Yoshindo has also been a great ambassador for swordmaking outside of Japan. He has given extended demonstrations of forging and lectures all over America, exhibited at several private galleries and has had swords displayed in The New York Metropolitan and Boston Museums.

Yoshindo has also built forges in Dallas and San Francisco in an effort to further understanding of the Japanese sword in the west. He travels regularly to the United States to support Japanese sword events and attend knife shows. Yoshindo continues to head the Yoshihara family of smiths from the Nihonto Tanren Dojo, where he currently has three apprentices in training.

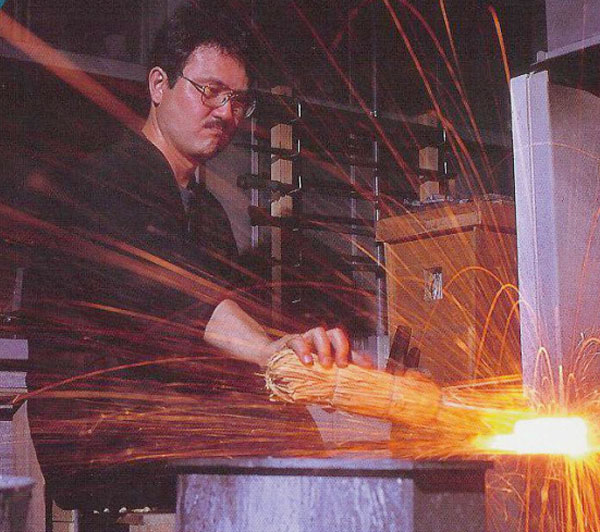

Yoshindo performing yaki ire– The quenching process

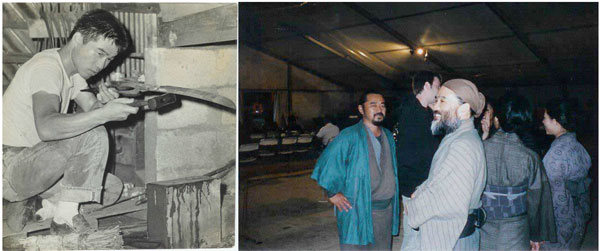

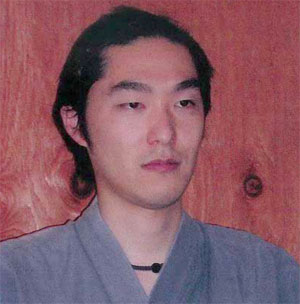

Yoshihara Shoji (Kuniie III)

Yoshihara Shoji

Yoshihara Shoji is the grandson of Kuniie, son of Masahiro, and the younger brother of Yoshindo. Shoji also uses the art name Kuniie, and is a third generation Yoshihara smith, as is Yoshindo.

Shoji however, began making swords before Yoshindo, working from a young age in the forge with their grandfather while Yoshindo continued the family business of tool production with their father Masahiro (Kuniie II). Shoji, after graduating from high school, chose to work at a car dealership for six months, before deciding to return to the workshop with his grandfather to become a full-time swordsmith.

Shoji initially used his own name to sign his work until he took the Kuniie name in 1982 after being awarded the rank of mukansa. Before taking the name Kuniie he also

occasionally used the name Tsuneie, particularly during the years 1970 to 1972.

Shoji’s early styles of forging are in the soshu tradition and in the styles of Kiyomaro and Kotetsu. He later changed to the Bizen tradition. Shoji was the youngest ever recipient of the Award for Effort in 1966 when he was 21, and went on five years later to be the youngest ever recipient of one of the first prizes, the Mainichi Newspape Award, when he was 26.

A young Shoji making swords On the set of the last samurai

When he was 37, he was awarded the title of mukansain in 1982. Before becoming mukansa, Shoji has received many accolades:

- Bunkacho Director’s Award three times

- NBHTK Honorary Chairman Award three times

- the Kunzan Award

- the Kanzan Award

- the Award for Excellence twice

- and the Award for Effort twice.

Shoji has also taken orders for his swords from Ise shrine and was designated an Important Living Cultural Property in the ward where he lives, Katsushika ward, Tokyo.

In 2002 he played a cameo role in the Warner Brothers movie The Last Samurai as the village swordsmith to the local warlord. Because of this recognition Hollywood celebrities have visited his workshop and purchased his swords.

He is currently an appointed swordsmith instructor for the NBTHK, an instructor of first stage sword polishing for swordsmiths, and deputy head of the All Japan Swordsmiths Association, and seventh dan in the art of iaido: the art of drawing and cutting with a Japanese sword. He continues work from his workshop, the Nihon So Tanto Jo (named after his grandfather’s forge in Setagaya, where he was born) at his residence in Nishi Mizoguchi.

Ono Yoshimitsu

Ono Yoshimitsu

Ono Yoshimitsu was born Yoshikawa Mitsuo in Niigata on October 16, 1948. He apprenticed himself to Yoshindo and Shoji Yoshihara at the Nihonto Tanren Dojo in 1969. H was trained by both brothers during his apprenticeship but was given the Yoshicharacter from Yoshindo along with mitsufor his swordsmith name by the late Dr. Kanzan Sato.

He received his swordsmith’s licence in 1975. In 1976 after finishing his apprenticeship, he returned to Niigata and opened his own workshop.

In 1984 and 1989 he received orders for his swords from Ise shrine. These ‘sacred swords’ were made with due ceremony. Yoshimitsu became a mukansasmith in 1987 after winning the Prince Takamatsu Award four times in a row (five times in total). In 1991, the Hayashibara Art Museum in Okayama Prefecture held an exhibition solely devoted his work.

It was entitled Ono Yoshimitsu’s World of Juka Choji. Yoshimitsu went on to appear in a television program produced in English by the Hayashibara Foundation. Entitled Takumi, it focuses on the spirituality of the Japanese sword and its links with other areas of Japanese culture.

In 1994 he received an order for a tachi from the Shosoin in Nara. The original Shosoin had been an imperial repository since 756 AD.

Yoshimitsu is so enthralled by the Yamatorige (a Japanese national treasure ko bizen tachi) that he devotes much of his swordsmithing time to recreating it over and over in a spiritual search for the way in which the blade was originally produced. It is not an exact copy. He has modified some of the features to suit his own interpretation, but the essence of the original strongly remains.

Yoshimitsu’s research into swordmaking does not stop there. In a further effort to recreate the visual appearance of older blades, he has similarly forged works polished by different schools and by varying standards of polishers in order to analyze the effects on the finished blades. He conducts this research at his own expense. Yoshimitsu continues to make swords and pursue making the Yamatorige at his forge in Niigata and the Hayashibara Museum forge in Okayama.

Shinohara Yoshihiro

Shinohara Koji

Unfortunately, Shinohara Koji (art name Yoshihiro) is a smith who has been forced to temporarily stop making swords and become the proprietor of an izakaya

(Japanese bar) in order to earn a living. Born in 1949 in Saitama prefecture, he had been interested in Japanese swords from childhood.

He joined the Yoshihara Nihonto Tanren Dojo in 1972, and went on to complete his apprenticeship. Although Shinohara received his swordsmith’s licence in 1977, he stayed at the studio until 1979, when he felt confident enough to open his independent forge in Saitama.

In 1978 his first entry into the NBTHK’s Annual exhibition won the Award for Effort. In 1980 and 1981, Shinohara won the NyusenAward (deemed worthy of exhibition). He went on to win yet another Award for Effort in 1982, but around this time had to stop making swords for economic reasons.

He hopes to return to swordmaking in the near future.

Fujimoto Yoshihisa

Fujimoto Kazuhisa

Fujimoto Kazuhisa was born June 23, 1962. He entered the Yoshihara studio as an apprentice in 1979 and received his swordsmith’s licence by 1984. Once he graduated from the Yoshihara studio, he opened his own forge in Okayama prefecture and took the art name Yoshihisa.

Since opening his own forge he continues to work in the Bizen tradition, particularly in the style of the Ichimonji school.

He frequently gives forging demonstrations at the Hayashibara Museum in Okayama. Yoshihisa has regularly received awards at the NBTHK’s annual

swordsmiths’ exhibition. He has won the Award for Excellence three times, the Award for Effort three times and the NyusenAward twelve times.

Nagaoka Masaie

Nagaoka Masaie

Nagaoka Masaie is a former student of Shoji. His given name is Noguchi Hitoshi. Born in 1963, he joined Kuniie as an apprentice in 1985. He felt it was in his blood to become a swordsmith, as was his father (Yukiharu of the Taguchi school of smiths). Yukiharu, impressed by Shoji’s reputation and skill, sent Masaie to the Nihon So

Tantojo for training.

A smith of great promise, Masaie won the Kunzan Award (one of the first prizes) on his second entry to the exhibition. On his first entry he was Awarded Nyusen. He went on to win the Award for Effort twice and the Award for Excellence twice.

However, due to the difficulties of being a swordsmith in modern Japan, he has had to continue the craft parttime—taking a corporate position to supplement his swordsmithing income. This is not an isolated case. There are many young talented smiths who take up the craft, only to find that they are unable to support themselves.

An average apprenticeship is usually about five years on minimum or no wage, but many stay longer in order to perfect their skills and out of respect to their teacher before leaving to start their own studios.

Kubo Yoshihiro

Kubo Yoshihiro

Kubo Yoshihiro was born March 19,1965 on the small island of Amami Oshima; part of Kagoshima prefecture just off the southern most island of Japan, Kyushu. H graduated from high school in 1983 and entered directly into Chiba University to pursue a degree in agricultural chemistry.

Yoshihiro graduated from university in 1987 and went on to graduate school. While at graduate school he watched a program in which the late Living National Treasure swordsmith, Sumitane Masamine, discussed the problems of trying to recreate the way swords of the Kamakura period were made.

Being a scientist and possessing a great interest in Japanese swords, Yoshihiro was intrigued by the problems facing swordsmiths and eager to find a solution. He went to the Nezu sword club, where he met mukansasword polisher Okisato Fujishiro. Once Yoshihiro expressed his interest in becoming a swordsmith, Okisato introduced him to

Yoshindo, who accepted him as a student.

Upon completion of his graduate degree, Yoshihiro immediately joined the Yoshihara Nihonto Tanren Dojo as an apprentice. In 2001, after receiving his swordsmith’s

licence, he opened his own swordsmith training workshop called The Yoshihiro Nihonto Tanren Dojo in Hiroshima.

He is currently part of a group of eight smiths, called the Mura-kumokai. Mura-kumo is the original name of the Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi—the sword that makes up part of th imperial regalia, along with the mirror and the jewel. This group, although they come from completely separate schools, exchange ideas and exhibit collectively around Japan.

Kubo san has since been awarded tokusho prizes at the annual sword-forging competition and in 2007 was awarded the NBTHK Chairman’s Award

Yoshihara Yoshikazu

Yoshihara Yoshikazu

Born in 1967 in Tokyo, Yoshikazu is the fourth generation in the Yoshihara family of swordsmiths and is the great-grandson of Kuniie I. Yoshikazu, like his father Yoshindo, uses his own name to sign his blades. He became his father’s apprentice in 1985, but like his father and his uncle, his exposure to the swordsmith’s workshop actually came much earlier than that, as he spent much time there when he was a child.

Yoshikazu obtained his swordsmith’s licence in 1990. Even though he has completed his five-year apprenticeship many years ago, he prefers to stay with his father at the Nihonto Tanren Dojo, and will eventually succeed his father in the running of it.

Yoshikazu hopes that in turn his own son, Akira, will also eventually take over the family business. Yoshikazu has always been a remarkable smith, and like his father and uncle before him he has made an indelible impact on the Japanese sword world, and won numerous awards.

In 2003 at the age of thirty-six, after winning the Prince Takamatsu Award for the third time in his career, he was elevated to the rank of mukansa. Yoshikazu is the youngest smith ever to receive this accolade. Although Yoshikazu can work in other traditions of swordmaking, he personally likes the flamboyant style of the Kamakura period, Ichimonji school.

In the Japanese sword world, there is a tendency to believe that the older swords are better swords. Yoshikazu does not believe this is the case. He feels that the Japanese sword has always been a progression of technology, and that smiths today are just as (if not more) skilful as the smiths of 800 years ago. He notes that historical value and technical skill are two different things.

It is his intention to continue pushing the boundaries of sword technology, continuing its evolution, as did generations of smiths before him.

Sato Yoshiaki

Sato Yoshiaki

Born 1974 in Tokyo, Sato Yoshiaki entered the Yoshihara studio at the age of twenty-one, obtaining his swordsmith’s license in 2000. Although the majority of his training was in the Bizen tradition, he now prefers to work in the soshu tradition. Yoshiaki is also skilled at decorative carving (horimono).

Yoshiaki’s interest in Japanese swords began at a young age. He decided early on that he wanted to become a swordsmith and make them himself.

He feels that Japanese swords are the world’s foremost cutting weapon. Yoshiaki does not enter the annual swordsmiths’ competition as he feels that sword appreciation is a personal matter.

Since leaving the Yoshihara studio, he has started his own workshop in Higashi Mizumoto, Katsushika ward, Tokyo.

Yoshiaki shares this studio with another former Yoshihara apprentice, Oda Kuzan.

Oda Kuzan

Oda Kuzan

Kuzan was born in Nagasaki on the island of Kyushu in 1942. He left high school at sixteen to pursue a career in the Japanese airforce. After a brief stint, he decided to learn sword polishing from his uncle, Yasuo Oda in Kyushu. When he was 19 he moved to Tokyo in search of work and trained as a toolmaker.

When he was 32, he decided to relocate to America. He was to spend the next 20 years living in the United States before returning to Japan in 1993.

Kuzan was already friends with Yoshindo Yoshihara before he left for America. When Yoshindo was demonstrating swordmaking in Dallas, Texas, Kuzan went to see his old friend. On this occasion he asked Yoshindo for an apprenticeship, but Yoshindo refused. As Kuzan did not want to apprentice with any other swordsmiths, he repeatedly asked Yoshindo if he could become his apprentice.

Yoshindo always refused, saying he would always be his friend, but he could not take him as an apprentice.

When Kuzan moved back to Japan, he approached Yoshindo once more and pleaded to be accepted as an apprentice. He told Yoshindo that at 52 years of age, this was his last chance to fulfil a lifelong dream of becoming a swordsmith. Yoshindo relented, and Kuzan when on to complete his apprenticeship and get his swordsmith’s licence in September 1998.

He continues to work in a workshop he shares with Sato Yoshiaki, another former student of the Nihonto Tanren Dojo in Higashi Mizumoto, Tokyo.

In 2003, Kuzan was approached by the Japanese TV program Seeds of Trivia. In the program, a 45 semi-automatic handgun was fired from a five meter distance, directly at the cutting edge of Kuzan’s blade. High-speed photography was used to record the results. The bullet was completely cut into two, with absolutely no damage to the blade.

Kuzan was challenged once again. The test was a 5.0 calibre machine gun. This time the sword appeared to be shattered by the rapid succession of gunfire. However, the slow motion footage revealed astonishing results. The sword had completely sliced six full metal jacket rounds in two before succumbing to the onslaught of the machine gunfire.

Takano Yukimitsu

Takano Yukimitsu

Takano Yukimitsu is Ono Yoshimitsu’s former student. Born October 15, 1952 in Ibaraki prefecture, Takano Hiroyuki moved to Tokyo with his parents at the age of two. He had developed a keen interest in Japanese swords at a young age and began studying them diligently soon after he left high school.

As a supplement to his sword study, he took a part-time job at the Yoshihara Tanren Dojo as an assistant. It was during this time he met

Ono Yoshimitsu. Takano was so impressed on the first occasion he saw Yoshimitsu produce a copy of the Yamatorige that he immediately asked Yoshimitsu if he would

accept him as his student.

Yoshimitsu accepted Takano as a student in December 1986. After receiving his swordsmith’s licence on April 4, 1992, Takano took the art name Yukimitsu. He has been entering the Shinsakutoten since 1996, where he has repeatedly attained the rank of Nyusen.

He also regularly enters his blades into the annual exhibition of smiths from the Kanto branch of the Japanese Swordsmiths Association at the famous Yasukuni shrine in Kudan, Tokyo. Takano doesn’t make many long swords, as in today’s economic climate they are difficult for relatively unknown smiths to sell. Since becoming an independent smith, Takano has chosen to work in the Gassan style of swordmaking.

Gassan are a school of smiths whose work dates back to the Kamakura period. They were known for their ayasugi hada (Japanese cedar grain pattern), a characteristic Takano uses in his blades. Takano runs a successful kogatana (traditional utility knife) school out of his forge in Adachi Ku, Tokyo, very close to the Nishi Arai Daishi Shrine.

He teaches courses for people interested in understanding the swordmaking process.

———————————————————————————————————————-

This article was written by Paul Martin (few years ago) and made possible due to the great help he received from many people.

“I would like to thank The Yoshihara family for supplying many photographs, Yoshindo Yoshihara, Leon and Hiroko Kapp for the use of images from Modern Japanese Swords and Swordsmiths. Okisato Fujishiro for the use of his images. Chris Bowen for his hel and oshigata. Abe Kazunori for his help and oshigata. Tom Kishida for allowing me to use his images. Tamio Tsuchiko for the use of his images, and all of the swordsmiths for their time and patience.

Note : According to Paul, this article is a bit out of date now because Kubo Yoshihiro’s own student has been taking some top prizes of his own recently but i still believe it’s a stunning piece of research !

We had a very interesting conversation with Paul back in 2011. Make sure you read that as well 🙂

Furthermore you can find Paul at The Japanese Sword or at his Facebook page.